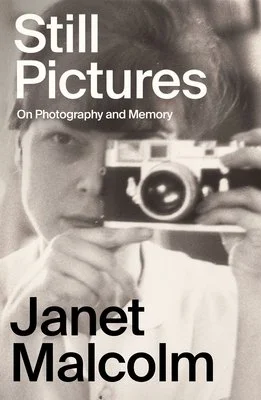

Book Review: ‘Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory,’ by Janet Malcolm

By P. D. Quaver

When I turned a page of my morning New York Times a couple of years ago to find Janet Malcolm's life being soberly summed up, I felt more than the usual pang one experiences at the loss of someone who has enriched one's life with her artistry: I felt as if I had lost a friend. This was all the more surprising because—though I had eagerly devoured the many pieces Ms. Malcolm had written over the years, either in the New Yorker or in their republished incarnations as slim, concise and beautifully produced books—she had never written a memoir.

Her writing was celebrated in much the same way as Joan Didion's. Exemplary, penetrating investigations and meditations on topics contemporary, or—occasionally—idiosyncratically quirky. Prose in which every sentence rewards one's attention, language to be savored, journalism as high art. And yet Didion's passing didn't leave me feeling bereft. Because all writers, whether of journalism, fiction or memoir, can't help but reveal themselves to some extent. And Didion, for all her virtuosity, always seemed to gaze at her subjects—be they stoned hippies of the Haight, or her own ancestors—with the chilly Olympian detachment of the securely well-born. But Malcolm peeled away the poses and pretensions of not just her subjects, but of herself as well; for her to investigate a notorious murderer (one of her recurring subjects) was to give not just the perpetrator, but her own motivations and biases, the third degree. It gave all her writing a meta complexity, and her bracing honesty could be breathtaking; as Ian Frazier, her colleague at the New Yorker and close friend, wrote in his touching introduction to this book, "She never wrote a bogus sentence."

Perhaps this is why she shied from writing a standard memoir, for surely she would have balked at having to impose some artificial structure on life's messy and ineffable complexities. So this book is doubly precious, Malcolm's posthumous gift to us. Unfinished at her death (and with a final chapter penned by her daughter), it uses photographs from Malcolm's life to launch her on flights of musing. On the people in her life, some important (her parents are vividly and lovingly brought to life), some as forgettable as the photos themselves. Most of which, Malcolm writes, were "taken from too far away, of people whose features you can barely make out...[and yet] some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us."

It makes for a memoir as quirky and alive as life itself.

At times Malcolm even abandons her conceit—there’s a chapter called "Four Old Women" with no photos at all—just to follow a whim, and sketch a clutch of incidental, walk-on characters, one of which she scarcely knew but remained lodged in her memory. And everywhere that wonderful, probing intelligence, delight in humanity's infinite variation, leavened by a sly wit.

That mischievousness is in all her writing; it's one of the things that made me feel I knew her. She writes about a farm that took in boarders in the summer, where her parents yearly decamped. Janet and her sister Marie were always bored to tears. There seemed nothing to do all day but play croquet:

‘There was a girl named Gwendolyn who cheated at the game; she was always moving her ball or yours. In the evenings we and the four or five other families or couples staying at the farm gathered in the parlor. We played word games or Gwendolyn played the piano. She was pretty in a blond, sugary way. She played well. Marie and I hated her.’

Her parents were Czech immigrants who narrowly escaped the Nazis, arriving in New York in 1939 when Janet was almost five; there's a tiny snapshot of the three of them in a train window as they set off on their journey, her parents looking giddy with relief, little Janet with an expression on her face "which the Czech word mrzuty conveys more powerfully and succinctly than any of its English definitions: cross, grumpy, surly, sulky, morose, peevish."

The tiny photo ignites a small firestorm of fraught memories, one of which adds depth to Malcolm's masterly portrait of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in her book "Gertrude and Alice." She wrote about the pair's troublingly blithe indifference to the persecution, during the Nazi occupation, of other Jews in France; how Gertrude even invited Nazis to her legendary salons, and how (when things got too hot) the two of them comfortably sat out the war in a remote French village.

Malcolm pursued the story of Gertrude's and Alice's evasions with forensic zeal, giving the pair no quarter (and having her mischievous way with Gertrude's smug surety of her own literary genius). So it's fascinating to discover that Malcolm's own parents kept their background a secret from Janet and Marie, enrolled them in a Lutheran Sunday school as protective coloring in their new lives as Czech immigrants in Manhattan, and didn't reveal to them their own Jewishness until they had already absorbed the anti-Semitism of their childish peers.

It's just one of many confessional moments. One of my favorites, a coda to Malcolm's portrait of her mother, confides that she herself seems to have inherited her mother's charm. "Charmers want to know about you," she writes, "they ask questions, they are so interested...Did I become a journalist because of knowing how to imitate my mother?" And probing even deeper, remarks that both she and her mother often didn't really listen to the responses of those they had charmed. And reveals (mischievously!) that what would seem a mortal failing in a journalist is mitigated by the fact she always taped her interviews.

Perhaps Malcolm's most confessional chapter straightforwardly tells the story of an adulterous relationship. She begins by recalling some china she'd bought for the one-room unfurnished apartment she and her lover rented for their illicit luncheons, an Italian plate "decorated with a sort of faux folk art flower design." She continues cataloguing the articles with which they'd furnished their love nest, how some were stolen (including that plate, through an open window), and segues seamlessly to memories, some deeply personal, of the man she calls "G." (who would later become her husband).

Finally she concludes:

What about the Italian plate I described at the beginning of this piece? What did it mean to me? Why did it come to mind after so many years? I know the answer but--like a balky child--I find myself reluctant to give it...The prerogative of cowardly withholding is precious to the most apparently self-revealing of writers. I apologetically exercise it here.

But really, dear Janet—no need to apologize! For I am already beyond thankful for the bounty of what this most "apparently self revealing of writers" has chosen to reveal of her thoughtful, questioning self, in this book and so many others.